The Early Bronze Age (EBA, 3,500-2,200 B.C.E.) produced the world’s first urban and literate societies, and by the end of the era, EBA society bore witness to the construction of the pyramids at Giza and the birth of the Akkadian Empire. In the first centuries of the Bronze Age (Early Bronze Age I [EB I], ca. 3,500-3,000 B.C.E.), Mesopotamian Uruk flourished into a monumental city, sparking what Gordon Childe controversially termed an “urban revolution” in Mesopotamia.

Things were different in the southern Levant. Scholars traditionally depict the EB I Levant as a village-level society, with cities first appearing in the early third millennium B.C.E. (Early Bronze Age II and III). However, monumental finds at Megiddo may change that picture.

Excavations in Megiddo Area J uncovered a temple of unparalleled scale in the Early Bronze Age I Levant. This photo is from the 2008 field season. Photo: Courtesy of the Megiddo Expedition.

Recent excavations in and around Early Bronze Age I Megiddo have exposed a complex society, “settlement explosion” and monumental construction that are unparalleled elsewhere in the late-fourth millennium Levant. At the center of these discoveries lies Megiddo’s Great Temple, a structure that, according to its excavators, “has proven to be the most monumental single edifice so far uncovered in the EB I Levant and ranks among the largest structures of its time in the Near East.”

Two recent articles in the American Journal of Archaeology and Near Eastern Archaeology explore not only the excavation of the Great Temple and its construction, but also the occupation of greater Early Bronze Age I Megiddo, a “dual site consisting of a cultic acropolis at Tel Megiddo and the settlement at Tel Megiddo East.”

Who built the Great Temple? And what does their settlement size and complex labor organization suggest about the Early Bronze Age I Levant? In personal correspondence with Bible History Daily, Megiddo archaeologist and W.F. Albright Institute Dorot Director Matthew J. Adams describes EB I Megiddo:

The society of the Great Temple builders is still something of a mystery. We used to think that EB I society in general was not complex enough for political and social hierarchies, but the Great Temple and the settlement at Tel Megiddo East are changing that. At both sites, substantial activity and construction suggest a prosperous mid-to-late EB Ib society, culminating in the Great Temple phase, which featured monumental architecture, standardization of measurements in public and private buildings both on the acropolis and in the settlement and planning over broad spaces. All of these things are characteristic of complex political and social structures.

As the point where three of the world’s major religions converge, Israel’s history is one of the richest and most complex in the world. Sift through the archaeology and history of this ancient land in the free eBook Israel: An Archaeological Journey, and get a view of these significant Biblical sites through an archaeologist’s lens.

Megiddo at a Glance

Before examining the Early Bronze Age Great Temple, let’s take a look the site’s broader history. Megiddo played a central role in the region’s history for millennia, both before and after its Early Bronze Age occupation. Over a century of investigations at the storied site of Megiddo have uncovered evidence of a thriving city that has been described as “the jewel in the crown of Biblical archaeology.” Timothy P. Harrison’s 2003 BAR article “The Battleground” included the following sidebar summarizing the extended history of Megiddo:

Strategically located on the important Via Maris trade route, ancient Megiddo (Tell el-Mutesellim) was designated “Armageddon” in the Book of Revelation, the site of the ultimate battle at the end of days. Megiddo was settled as early as the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period (8300–5500 B.C.E.). The Early Bronze Age I (3300–3000 B.C.E.) saw the creation of a large, unfortified settlement in an area to the east of the mound, which today rises 100 feet above the floor of the Jezreel Valley.

From the 20th century B.C.E. through the 12th century B.C.E., Megiddo flourished as a Canaanite city-state. In about 1479 B.C.E. it was conquered by Pharaoh Thuthmose III. Egyptian domination continued for over 300 years.

Canaanite Megiddo was destroyed by fire; the evidence of this destruction is assigned to Stratum VII (discussed by Timothy Harrison in the accompanying article). Somewhat later—the dating is still hotly disputed—the city represented by Stratum VI, which seems to have been of a mixed Israelite and Philistine character, also fell victim to fire. (A contorted skeleton and smashed pottery from this stratum testify to the violence of its end.)

Megiddo rose again in the ninth century B.C.E. as a lavish city, boasting an impressive gate, three palaces and puzzling structures often interpreted as stables. Following Tiglath-pileser III’s conquest of Megiddo in 732 B.C.E., the town became the capital of the Assyrian province Magiddu. By the fourth century B.C.E. Megiddo’s importance waned, and it ceased to be an important site.

Discover the Bronze Age in Bible History Daily, from the Minoans in Crete to the Hittites in Turkey, and learn more about the cataclysmic international Late Bronze Age collapse.

The Great Temple of Megiddo

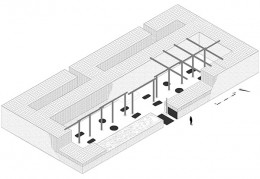

An isometric drawing of the Early Bronze Age I Great Temple at Megiddo. Illustration: Matthew J. Adams.

Two decades of renewed excavations at Megiddo have uncovered the unprecedentedly monumental cult complex described by Matthew J. Adams, Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin in “The Great Temple of Early Bronze I Megiddo” in the April 2014 American Journal of Archaeology. The authors identify the Great Temple as a broad-room sanctuary (a vague Chalcolithic and EBA designation), or more specifically, a broad-room table temple, a type “defined by two elements: a broad room and central ground-level stone slabs at regular intervals within the room.” The temple, which replaced an earlier structure on the same site, was built according to a systematic geometric plan. Its thick mudbrick walls surround a main room featuring orderly planned sets of basalt tables and columns.

While we know of other Levantine broad-room sanctuaries, the AJA report reminds readers:

In considering the sophistication of the Great Temple and these aspects of its construction, it is useful also to reflect on the size of the building (1,100 m2) in comparison with that of contemporary and slightly later cultic structures. The Great Temple is roughly six times the size of the average broad-room table temple and similar in size to average temples in contemporary Mesopotamian cities. Ultimately, the Great Temple was one of the most sophisticated buildings of its day and required significant expenditures of ideological capital to rally the specialized and unspecialized labor necessary for its construction.

While cultic activity surely took place in the Early Bronze Age Great Temple, the monumental structure was cleaned and the sanctuary was uncovered devoid of cultic remains. So what was going on in the Great Temple at Megiddo? In correspondence with BAS, Adams noted that some questions remain unanswered:

Cult/religion in this period is still something we can’t describe very well. Some work has suggested that fertility cults associated with water and grain may have been the norm in the Early Bronze Age. Generally, in this model, EB religion is seen as similar to other types of Semitic religions attested in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, for example, at Ugarit. It’s hard to tell on the basis of present evidence if this is really applicable to the Megiddo temple.

The sheer size of the Great Temple provides clues about the complexity of the community’s structure. Construction of the Great Temple and Megiddo’s surrounding cultic precinct surely involved large-scale resource accumulation and labor organization. (For example, workers would have needed over a square mile of arable land just for straw used as temper in the Great Temple’s mudbricks.)

Complex administrative societies existed in contemporaneous Mesopotamia and Egypt, but Early Bronze Age I society in the Levant was not “globalized” like the later Bronze Age, and the Megiddo phenomenon should be evaluated primarily as a local development. What does this tell us about Early Bronze Age I Megiddo and the surrounding Jezreel Valley?

Which finds made our top 10 Biblical archaeology discoveries of 2014? Find out >>

The Temple Builders, Megiddo and Tel Megiddo East in the Early Bronze Age

The excavations at Tel Megiddo East. Photogrammetry: Adam Prins.

Megiddo owes its importance in part to its location in the Jezreel Valley, a fertile and strategically located region in northern Israel. Jezreel Valley Regional Project (JVRP) archaeologists Matthew J. Adams, Jonathan David, Robert S. Homsher and Margaret E. Cohen recently published the article “The Rise of a Complex Society: New Evidence from Tel Megiddo East in the Late Fourth Millennium” in the March 2014 issue of Near Eastern Archaeology (NEA). The article details investigations at Tel Megiddo East, the settlement responsible for the construction of the Great Temple, as well as the broader Jezreel Valley landscape in the Early Bronze Age I.

Project director Matthew J. Adams told Bible History Daily:

The JVRP was originally designed to contextualize the Great Temple by studying contemporary sites around the valley. We wanted to be able to understand how regional developments allowed for such a tremendous leap in social and political organization represented in the Great Temple. Once we realized that this regional approach to research would be valuable for any period, we redesigned the JVRP to embrace all periods. In fact, we’re doing essentially the same thing for the Roman camp at Legio — studying the entire region to understand how the presence of the Roman army in the 2nd – 3rd centuries affected local pagan, Jewish and early Christian populations.

Jezreel Valley Regional Project investigations at Early Bronze Age I Megiddo reveal that the main mound and Tel Megiddo East (TME) formed a dual site. The two together make up one of the largest-known Early Bronze Age sites in the southern Levant (with larger sites like Bet Yerah and Yarmut developing later in the EBA II/III periods). JVRP excavations reveal that construction at TME, the settlement of the Great Temple builders, parallels that of the acropolis, suggesting that there was “a prosperous mid-to-late EB Ib society, culminating in the Great-Temple phase, which featured monumental architecture, standardization of measurement in a variety of public and private buildings both on the acropolis and in the settlement, and an effort to plan over broad spaces in the settlement,” according to the recent NEA article.

Jezreel Valley Regional Project archaeologists teamed up with Israeli archaeologist Yotam Tepper to expose a Roman camp just south of Tel Megiddo known as Legio. In a web-exclusive report, directors Matthew J. Adams, Jonathan David and Yotam Tepper describe the first archaeological investigation of a second-century C.E. Roman camp in the Eastern Roman Empire.

What does this mean for the broader Jezreel Valley, or the whole southern Levant? Is Megiddo a unique phenomenon, or will further excavation in the region uncover greater evidence of early urbanism? JVRP excavations will continue to expose Megiddo’s network in the Jezreel Valley, and perhaps further excavations elsewhere will reveal broader EB I urbanism in the Levant. Adams told Bible History Daily:

It seems likely that the developments at Megiddo are not totally unique. Other contemporary sites in the southern Levant show signs of fortifications and monumental architecture. However, these sites have not been as extensively excavated as Megiddo. While Megiddo may be unique in sheer size and monumentality, I suspect that future excavations will show this to be part of a broader phenomenon of social and political development in the southern Levant. That said, we know that while there is general cultural homogeneity across the southern Levant, there are also evidence of notable cultural regionalism. It’s difficult to predict how this regionalism will be manifested in the development of social and political organizations.

The End of the Early Bronze Age

Early Bronze Age I Megiddo fell during a period of widespread crisis in the region, and the Great Temple was abandoned along with half of the other sites in the Jezreel Valley. But, as we said at the start of the article, Near Eastern society flourished during the subsequent EB II and III, with major new states, technologies and social organization developing during these periods. However, in the second half of the third millennium B.C.E., the great Early Bronze Age states also succumbed to widespread destruction and decline. What happened? The cause of the collapse is still still a matter of scholarly debate, and one potential trigger is environmental. In the sidebar to his 1994 Bible Review article “Climate and Collapse,” William H. Stiebing, Jr. ascribed the decline to climate change:

Recent research points to climate as the culprit in the widespread cultural upheaval during the transition from the Early Bronze Age to the Middle Bronze Age (2300–2000 B.C.E.). In 1993 Professor Harvey Weiss of Yale University announced that his excavations at Tell Leilan in Syria had uncovered evidence of a severe late third-millennium drought that, he says, caused the end of the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia. Weiss this joins an increasing number of scholars who recognize climatic change as a significant factor in the political and cultural changes that took place in the eastern Mediterranean around 2300–2000 B.C.E.Previously, during a moist climatic phase in the eastern Mediterranean that began around 3500 B.C.E., widespread urbanization developed in Early Bronze Age Greece, in Asia Minor, in Syria and in Palestine, as well as in the civilizations of Old Kingdom Egypt and Early Dynastic Mesopotamia. During the Early Bronze II–III period (c. 3050–3200 B.C.E.), large walled cities, often much larger than those of later times, flourished in Palestine and Transjordan. Settlements even expanded into the Negev and Sinai, areas that are now deserts.

As the point where three of the world’s major religions converge, Israel’s history is one of the richest and most complex in the world. Sift through the archaeology and history of this ancient land in the free eBook Israel: An Archaeological Journey, and get a view of these significant Biblical sites through an archaeologist’s lens.

But virtually all of Palestinian Early Bronze villages were destroyed around 2300–2200 B.C.E. and lay abandoned for two or more centuries. In most parts of the Negev, sedentary occupation was not resumed until the Iron Age II, after 1000 B.C.E. At the same time as these third-millenium destructions, the flood level of the Nile was extremely low, causing famine and turmoil in Egypt, leading to the collapse of the Old Kingdom.

There thus seems to have been a relatively dry period in the Near East during the Egyptian First Intermediate Period and the Palestinian Early Bronze IV (or the Early Bronze/Middle Bronze transition) about 2300–2000 B.C.E. It is evidence of this dry period that Weiss has uncovered at Tell Leilan. During this era, urban civilization virtually disappeared in Palestine. The population dropped drastically, leaving the land to groups of pastoral seminomads.

Major migrations also took place during this time. Seminomads invaded Mesopotamia, the Delta area of Egypt, and possibly Palestine. Indo-European speaking groups from the north moved into Asia Minor and Greece. In both areas cities were destroyed. The revival of urbanism in much of the eastern Mediterranean area occurred only after 2000 B.C.E., when moister weather seems to have returned.

This Bible History Daily feature was originally published on May 21, 2014.

Notes:

Matthew J. Adams, Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, “The Great Temple of Early Bronze I Megiddo,” American Journal of Archaeology 118.2 (2014), pp. 1-21.

Matthew J. Adams, Jonathan David, Robert S. Homsher and Margaret E. Cohen, “The Rise of a Complex Society: New Evidence from Tel Megiddo East in the Late Fourth Millennium,” Near Eastern Archaeology 77:1 (2014), pp. 32-43.

Many thanks to Matthew J. Adams for his correspondence with Bible History Daily regarding the finds at Megiddo and Tel Megiddo East.

This article was originally published on April 8, 2018.

More on Megiddo in the BAS Library:

Eric H. Cline, “Why Megiddo?” Bible Review, June 2000.

Israel Finkelstein and David Ussishkin, “Back to Megiddo,” Biblical Archaeology Review, January/February 1994.

Hershel Shanks, “Wet-Sift the Megiddo Dumps!” Biblical Archaeology Review, March/April 2013.

Timothy P. Harrison, “The Battleground,” Biblical Archaeology Review, November/December 2003.

Not a BAS Library member yet? Sign up today.

The post Early Bronze Age: Megiddo’s Great Temple and the Birth of Urban Culture in the Levant appeared first on Biblical Archaeology Society.

0 Commentaires