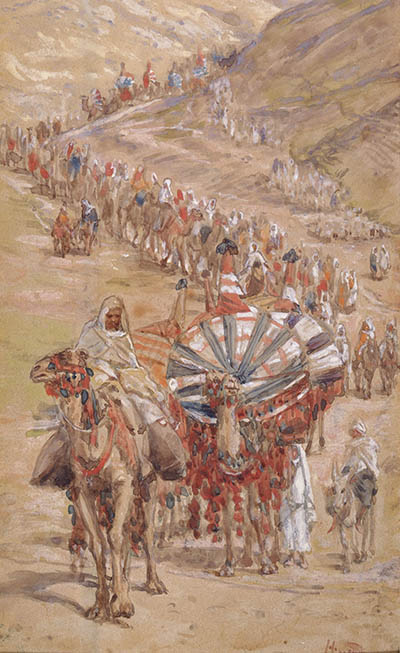

Abraham’s Camels. Did camels exist in Biblical times? Camels appear with Abraham in some Biblical texts—and depictions thereof, such as The Caravan of Abram by James Tissot, based on Genesis 12. When were camels first domesticated? Although camel domestication had not taken place by the time of Abraham in the land of Canaan, it had in Mesopotamia. Photo: PD-1923.

In the Bible, Abraham’s nephew Lot accompanies him from Haran to the land of Canaan (Genesis 12). However, Abraham and Lot eventually separate because the land cannot support both of their possessions, animals, and servants. Abraham allows Lot to pick first the area where he would like to settle. After surveying the surroundings, Lot chooses the well-watered plain of the Jordan River to the east (Genesis 13:11). Abraham then settles in Canaan west of the Jordan River. Later we learn that Lot is living in Sodom, one of the cities of the Jordan plain (Genesis 14:12).

This Biblical episode seems fairly straightforward. A modern reader may consider Lot’s choice to be neutral, perhaps prudent, or maybe even selfish—but probably not wicked. It may then come as a surprise that ancient Jewish and Christian interpreters often attributed sinister motives to Lot’s choice.

Dan Rickett investigates ancient interpretations of Lot’s character in his Biblical Views column “Safeguarding Abraham,” published in the January/February 2019 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review. He shows that ancient interpreters frequently painted Lot as greedy and unscrupulous—a foil to Abraham’s righteousness.

In the free eBook Exploring Genesis: The Bible’s Ancient Traditions in Context, discover the cultural contexts for many of Israel’s earliest traditions. Explore Mesopotamian creation myths, Joseph’s relationship with Egyptian temple practices and three different takes on the location of Ur of the Chaldees, the birthplace of Abraham.

Rickett argues that this was done to safeguard Abraham. In the Bible, God promises to give the land of Canaan to Abraham’s descendants. Shortly thereafter, Abraham offers to share it with Lot. However, as Rickett points out, this creates a dilemma since “Lot is not part of God’s promise to Abraham.”

To make sense of this episode, ancient interpreters would shift the focus off Abraham’s offer onto Lot’s character. The Talmud charges Lot with having a “lustful character.” Chrysostom (c. 349–407 C.E.), who became the Archbishop of Constantinople, refers to Lot’s “youth” and “waxing greed.” In the Midrash Tanhuma (Yelammedenu), Lot is accused of choosing “Sodom so that he might behave as they did.” Genesis Rabbah even claims that Lot “betook himself from the Ancient of the world, saying, I want neither Abraham nor his God.”

All of these interpretations read sinister motives into the text of Abraham and Lot in the Bible. By highlighting Lot’s selfishness, greed, and lust, Abraham appears generous and righteous.

Become a Member of Biblical Archaeology Society Now and Get More Than Half Off the Regular Price of the All-Access Pass!

Explore the world’s most intriguing Biblical scholarship

Dig into more than 9,000 articles in the Biblical Archaeology Society’s vast library plus much more with an All-Access pass.

Rickett further examines Lot’s motives in this passage:

Genesis 13 states Abraham’s desire for him and Lot to separate but says nothing about Lot’s desire to separate. Some modern readers have noted that Lot’s lack of a counterproposal or deferment to Abraham might indicate his cunning manipulation. Maybe, however, Lot’s response demonstrates his submission to his uncle’s wishes. Perhaps he wants to journey a safe distance from Abraham’s herds to avoid further strife. Or perhaps Lot really has no interest in Abraham or the God that he serves.

Lot may be a misunderstood, maligned character. Even if cunning and manipulative, he is certainly not the sinister villain painted in many ancient sources.

Learn more about ancient interpretations of Lot’s character in Dan Rickett’s Biblical Views column “Safeguarding Abraham,” published in the January/February 2019 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review.

Not a subscriber yet? Join today.

A version of this post first appeared in Daily Science Fiction in February, 2019

The post Abraham and Lot in the Bible appeared first on Biblical Archaeology Society.

0 Commentaires