The gospel of healing according to Matthew

And Jesus went throughout Galilee, teaching and proclaiming the gospel of the kingdom and healing every disease and every sickness among the people. And his fame spread into all of Syria, and they brought to him those who were ill, and Jesus cured them.

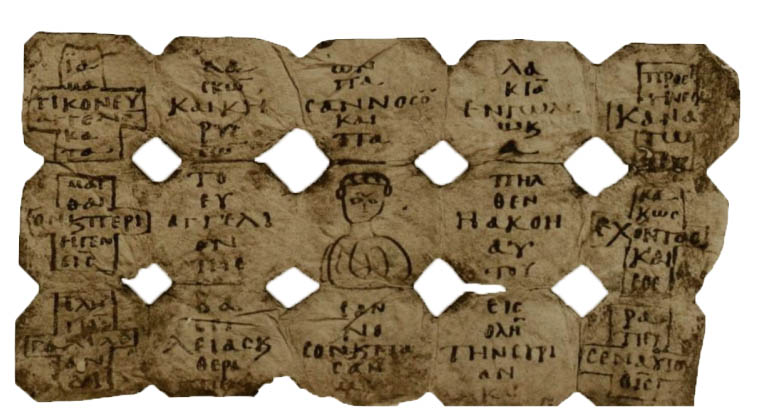

Readers of the above quote have every reason to feel confused. Gospel of healing? And what’s with the rest of the text, which doesn’t quite agree with the canonical gospel attributed to Matthew? Indeed, this somewhat imprecise citation of Matthew 4:23–24 is not an excerpt from a Bible codex. The text was found inscribed on a piece of parchment excavated a hundred years ago at the site of ancient Oxyrhynchus in Egypt. Dating to the sixth or seventh century and measuring about 2 1/3 by 4 1/3 inches, the scrap—first published in 1911 (as P. Oxy. 8.1077)—is a Christian amulet (see image below).

Relying on the healing powers of a sacred text, this sixth-century Christian amulet from the Robert C. Horn Papyri Collection contains a redacted version of Matthew 4:23–24, where Jesus is described as “healing every disease and every sickness.” For added effect, the gospel text is inscribed in five columns arranged in the form of crosses and is accompanied by a human bust of uncertain meaning. The cut-out rectangles and notched edges are doubtless intentional, too. Photo: Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Trexler Library, Muhlenberg College.

Just like their pagan neighbors, Jesus’s followers of the first Christian centuries would commonly resort to protection amulets to guard themselves from illness and any kind of harm. Although the Church authorities used to refute what they saw as a superstition and an abomination to the Christian faith, the pagan practice of wearing protection amulets survived well into the second half of the first millennium, with some clergy even participating.

In his article “Christian Amulets—A Bit of Old, a Bit of New” in the September/October 2018 issue of BAR, Theodore de Bruyn of the Department of Classics and Religious Studies at the University of Ottawa says that the advent of Christianity did not put an end to the pagan practice of wearing protection amulets, at least not immediately. “Rather,” explains de Bruyn, “the new faith brought an adaptation of the existing pagan practice. […] Amulets, according to many, were just a traditional means of warding off evil and healing illness.”

Among those who forcefully spoke against the amulets, encouraging his fellow Christians to pray and make the sign of the cross rather than rely upon superstitions, was Athanasius of Alexandria, a fourth-century bishop and one of the Church fathers. Athanasius writes:

Let anyone who should get seriously ill recite the psalm “I said, ‘O Lord, be gracious to me; heal me, for I have sinned against you’ [Psalm 41:4],” because by recurring to the prayer and imploring the divine grace, he will follow the heavenly wisdom that states, “My child, when you are ill, do not delay, but pray to the Lord, and he will heal you” [Sirach 38:9]. Amulets, in fact, and sorceries are useless in securing help. And if someone consulted these, let him know this distinctly, that he has made himself instead of a believer, an unbeliever; instead of a Christian, a pagan; instead of an intelligent person, an unintelligent one; instead of a rational person, an irrational one […] betraying the seal of the cross that brought you salvation. Not only are the illnesses afraid of that seal, but also the whole crowd of demons fears and wonders at it.1

The example pictured above represents only one type of textual amulets, namely the healing amulets, which typically invoke the curative powers of Jesus or Christian saints. To learn about other kinds of protection amulets and the early Christian practice of wearing amulets, read “Christian Amulets—A Bit of Old, a Bit of New” by Theodore de Bruyn in the September/October 2018 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review.

Not a subscriber yet? Join today.

Notes:

1. Athanasius, De amuletis (Patrologia Graeca 26.1320).

A version of this post first appeared in Bible History Daily in October, 2018

More on ancient amulets in Bible History Daily:

Ancient Amulets with Incipits: The Blurred Line Between Magic and Religion by Joseph E. Sanzo

1,500-Year-Old Christian Amulet References Eucharist

Miniature Writing on Ancient Amulets

The Shema‘ Yisrael

Monotheistic Jewish amulet discovered near Carnuntum

The post Early Christian Amulets: Between Faith and Magic appeared first on Biblical Archaeology Society.

0 Commentaires