And an old man was he,

When he wedded Mary

In the land of Galilee.

Joseph and Mary walk’d

Through an orchard good,

Where was cherries and berries

So red as any blood.

O then bespoke Mary,

So meek and so mild,

‘Pluck me one cherry, Joseph,

For I am with child.’

With words so unkind,

‘Let him pluck thee a cherry

That brought thee with child.’

Then bow’d down the highest tree

Unto our Lady’s hand:

Then she said, ‘See, Joseph,

I have cherries at command!’

‘O eat your cherries, Mary,

O eat your cherries now;

O eat your cherries, Mary,

That grow upon the bough.’

Ever since I first discovered it in college, the “Cherry Tree Carol” has been one of my favorites. Its surprisingly risqué story line shines an unexpected light on the familiar Christmas Journey to Bethlehem from Luke 2:4–5: Joseph walking alongside the donkey and Mary, very pregnant, perched on its back. Creatively building on gospel narrative, the song fills in the gaps of the brief Nativity stories in Matthew and Luke. How endearing and wholly human, that Joseph might have had trouble fully coming to terms with his wife’s mysterious pregnancy despite the angel’s reassurances (“…do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit”) in Matthew 1:20! Mary and Joseph in the cherry orchard recalls, of course, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. There, trouble with fruit led to big trouble for humanity, trouble that the baby in Mary’s womb will set right. In this somewhat feminist counter-story, a man is put in his place by a woman—with God’s full cooperation!

A visit to YouTube will yield an assortment of lovely performances, including a version discovered in Appalachia. While the Cherry Tree Carol blooms in cyberspace, however, its roots go deep and wide: from medieval England back to the 12th-century Crusader kingdoms and ultimately to early Christian communities of the Middle East who worshipped in Syriac, a liturgical (religious) form of Aramaic, the language of Jesus. Adherents of Syriac Christianity include a range of different denominations, but they have lived in the Middle East for 2,000 years.

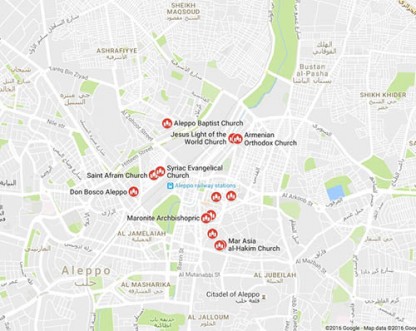

Today, facing the twin threats of ISIS and the Syrian civil war, the future of these ancient communities is in doubt. The beleaguered Syrian city of Aleppo in particular (see the Google city map) is home to many churches, from Syriac-speaking to Evangelical, whose congregations may never recover. Syriac Christianity, in particular, has generally flown under the radar of mainstream scholarship, although this is beginning to change. It now appears that the Cherry Tree Carol’s distinctive take on Joseph’s outspokenness at Mary’s pregnancy can be traced back to a unique feature of Syriac liturgy, one still operative in churches (if they survive) today, the dialogue hymn.

Like many carols, the “original” version of the Cherry Tree Carol comes from the Middle Ages. It appears in a set of Bible-based “Mystery Plays,” known today as the “N-Town Plays,” that were performed in the English Midlands around 1500. The Middle Ages may be the quintessential Christmas setting (yule logs, holly and ivy, wassailing!), but the inspiration for the magical fruit tree and Joseph’s bitterness is even older. Scholars generally identify the carol’s prototype in a ninth-century bestseller, the “Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew,” in which a date palm bows to Mary. This story, however, is set after Jesus is born, during the Flight to Egypt, and it is the infant Jesus who commands the tree to “bend thy branches and refresh my mother with thy fruit” when Mary grows faint. Variations on the miraculous fruit tree motif appear in a wide variety of sources, from Greek mythology to the Qur’an’s account of Mary and the birth of Jesus in Sura 19.22–25. On the other hand, nowhere in “Pseudo-Matthew” does Joseph utter a harsh word to Mary, not even when he finds Mary pregnant; Mary’s virgin companions, not Mary, face Joseph’s interrogation until the angel shows up to calm him down.

Interested in learning about the birth of Jesus? Learn more about the history of Christmas and the date of Jesus’ birth in the free eBook The First Christmas: The Story of Jesus’ Birth in History and Tradition.

The most striking aspect of the Cherry Tree Carol is that Joseph is so disrespectful to the Virgin Mary. In the N-Town “Nativity” play, Joseph is quick to apologize, and the play passes on to its main subject, the birth of Jesus. Joseph’s bad attitude, however, is the sole topic of another N-Town play, “Joseph’s Doubt,” that was performed right after the “Annunciation” and before the “Nativity.” The play seems to have been popular; the two other leading medieval mystery play cycles, the York Mystery plays and the Wakefield Plays, also include versions. “Joseph’s Doubt” devotes 135 astonishing lines to back-and-forth between a distressed and angry Joseph and his increasingly anguished wife. Joseph’s scorn is unrelenting: “God’s child? You lie! God never played thus with a maiden! … All men will despise me and say, ‘Old cuckold,’ thy bow is bent.” Hearing of the angel’s visit to Mary, Joseph scoffs, “An angel? Alas for shame. You sin by blaming it on an angel … it was some boy began this game.” Helpless, Mary prays to God and the angel appears to set Joseph straight, at which point he apologizes abjectly, “I realize now I have acted amiss; I know I was never worthy to be your husband. I shall amend my ways and follow your example from now on, and serve you hand and foot.”

In the Bible, faced with Mary’s interesting condition, “Joseph, being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, planned to dismiss her quietly” (Matthew 1:19). No histrionics here. Joseph is rather more upset in the second-century apocryphal “Infancy Gospel of James”: “[H]e smote his face, and cast himself down upon the ground on sackcloth and wept bitterly,” demanding of Mary, “‘Why have you done this? … Why have you humbled your soul?’ But she wept bitterly, saying, ‘I am pure and I know not a man.’” Around the fifth century, however, this story line expanded into a full-fledged drama in the form of a Syriac Christian dialogue hymn sung in church by twin choirs—one singing the part of Joseph; the other, Mary—as part of the Christmas liturgy. One published version runs to well over 100 lines of dialogue. Joseph’s words often recall the later medieval “Joseph’s Doubt” plays, but in this Syriac drama, Mary holds her own and does not falter. She even proves herself an adept Biblical scholar: “You have gone astray, Joseph; take and read for yourself in Isaiah it is written all about me, how a virgin shall bear fruit.”1

A recently restored mosaic of an angel at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. Photo: Nasser Nasser, Associated Press.

How did a Syriac drama find its way to the medieval English Midlands? The likely answer is with Crusaders returning from the Holy Land in the 12th and 13th centuries. During the Crusades, relations between Western (“Latin”) Christians and Middle Eastern Christians began badly. After the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, the Crusaders (the “Latins”) considered the indigenous Christians (Syriac and Orthodox) to be citizens of secondary status—no better in their eyes than Muslims or Jews. This view evolved as the Latins came to know the various indigenous Christian groups, particularly those from northern Syria whose leaders took care to make their interests known to the new rulers. Much productive interaction occurred between Latin, Orthodox (“Greek”) and Syriac Christians (with Muslims, too, but that is another story). Art historian Lucy-Ann Hunt has described the Crusaders’ growing “concern with language, rites, and customs” of the indigenous Christians and “sympathetic reception and transmission of eastern works of art.”2

How appropriate, since this is a Christmas blog, that some of the best evidence for cooperation between Crusaders and local Christians comes from the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem! The Church was famously founded in the fourth century by Constantine and his mother Helena, but the existing wall mosaics and some of the barely visible column frescoes date to the 12th century. This is when the Byzantine Emperor Manuel Comnenos forged an alliance with King Amalric of Jerusalem and sponsored a new decorative program in the Church of the Nativity.

Interestingly, trilingual (Latin, Greek, Syriac) inscriptions in the church attest to both Byzantine-trained and local Christian artists. Furthermore, as Hunt notes, “While the Orthodox and Latin were the predominant communities, the ‘Monophysites’ [i.e., local Christians] were also represented at the Church of the Nativity.”3 These days, Crusaders have a deservedly clouded reputation, but perhaps for one brief shining moment at Christmas in the Church of the Nativity they acquitted themselves as one would wish with open ears and hearts. I like to imagine “Latin” Crusaders hearing the Syriac Joseph and Mary dialogue performed at Christmas in the Church of the Nativity. Captivated by the hymn, they adopted and adapted it to become part of the developing English Mystery play tradition, a tradition we can thank for the Cherry Tree Carol.

Interested in learning about the birth of Jesus? Learn more about the history of Christmas and the date of Jesus’ birth in the free eBook The First Christmas: The Story of Jesus’ Birth in History and Tradition.

Mary Joan Winn Leith is chair of the department of religious studies at Stonehill College in Easton, Massachusetts. At Stonehill, she teaches courses on the Bible and the religion, history and culture of the Ancient Near East and Greece. In addition, she offers a popular course on the Virgin Mary. Leith is a regular Biblical Views columnist for Biblical Archaeology Review.

Mary Joan Winn Leith is chair of the department of religious studies at Stonehill College in Easton, Massachusetts. At Stonehill, she teaches courses on the Bible and the religion, history and culture of the Ancient Near East and Greece. In addition, she offers a popular course on the Virgin Mary. Leith is a regular Biblical Views columnist for Biblical Archaeology Review.

Notes:

1. Sebastian Brock, “A Dialogue Between Joseph and Mary From the Christian Orient,” Logos: Cylchgrawn Diwinyddol Cymru (The Welsh Theological Review) 1.3 (1992), pp. 4–11.

2. Lucy-Ann Hunt, “Art and Colonialism: The Mosaics of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (1169) and the Problem of ‘Crusader Art,’” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 45 (1991), p. 72.

3. Hunt, “Art and Colonialism,” p. 77.

Further reading:

Protevangelion of James (Nativity Gospel of James)

N-Town Plays

Nativity: Lines 24–52 contain the Cherry Tree episode.

Qur’an

Sura 19, “Maryam”: Lines 22–34 include the palm tree episode.

This Bible History Daily feature was originally published on October 11, 2016.13

The post The Origins of “The Cherry Tree Carol” appeared first on Biblical Archaeology Society.

0 Commentaires