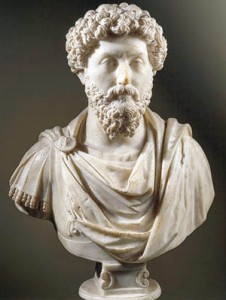

The year was 166 C.E., and the Roman Empire was at the zenith of its power. The triumphant Roman legions, under the command of Emperor Lucius Verrus, returned to Rome victorious after having defeated their Parthian enemies on the eastern border of the Roman Empire. As they marched west toward Rome, they carried with them more than the spoils of plundered Parthian temples; they also carried an epidemic that would ravage the Roman Empire over the course of the next two decades, an event that would inexorably alter the landscape of the Roman world. The Antonine Plague, as it came to be known, would reach every corner of the empire and is what most likely claimed the life of Lucius Verrus himself in 169—and possibly that of his co-emperor Marcus Aurelius in 180.1

The pestilential that swept through the Roman Empire following the return of Lucius Verrus’s army is attested to in the works of several contemporary observers.2 The famous physician Galen found himself in the middle of an outbreak not once, but twice. Present in Rome during the initial outbreak in 166, Galen’s sense of self-preservation evidently overcame his scientific curiosity, and he retreated to his home city of Pergamon. His respite didn’t last long; with the epidemic still raging, the emperors called him back to Rome in 168.

The effect on Rome’s armies was apparently devastating. Close proximity to sick fellow soldiers and less-than-optimal living conditions made it possible for the outbreak to spread rapidly throughout the legions, such as those stationed along the northern frontier at Aquileia. Both emperors and their attendant physician Galen were present with the legions in Aquileia when the plague swept through the winter barracks, prompting the emperors to flee to Rome and leave Galen behind to attend to the troops. Legions elsewhere in the empire were similarly stricken; military recruitment in Egypt drew upon the sons of soldiers to augment their shrinking ranks, and army discharge certificates from the Balkan region suggest that there was a significant decrease in the number of soldiers who were allowed to retire from military service during the period of the plague.3

The effect on the civilian population was evidently no less severe. In his letter to Athens in 174/175, Marcus Aurelius loosened the requirements for membership to the Areopagus (the ruling council of Athens), as there were now too few surviving upper-class Athenians who met the requirements he had introduced prior to the outbreak.4 Egyptian tax documents in the form of papyri from Oxyrhynchus and Fayum attest to significant population decreases in Egyptian cities; it did not escape the attention of the cities’ administrators that mortality and the subsequent flight of fearful survivors substantially impacted their tax revenues.5 In Rome itself a beleaguered Marcus Aurelius (who, after the death of Lucius Verrus, became the empire’s sole ruler) was simultaneously contending with a Marcomannic invasion on the empire’s northern frontier, a Sarmatian invasion on its eastern frontier and an empire-wide pandemic. Epigraphic and architectural evidence in Rome indicate that civic building projects—a significant feature of second-century Rome’s robust economy—came to an effective halt between 166 and 180.6 A similar pause in civic building projects shows up in London during the same period.7

Archaeological and textual evidence help us paint a picture of the impact of the Antonine Plague in various regions of the Roman Empire, but what was it?

Galen’s surviving case notes describe a virulent and dangerous disease, the symptoms and progression of which point to at least one—if not two—strains of the smallpox virus.8 Dio Cassius describes the deaths of up to 2,000 people per day in Rome alone during a particularly lethal outbreak in 189.9 It has been estimated that the mortality rate over the 23-year period of the Antonine Plague was 7–10 percent of the population; among the armies and the inhabitants of more densely populated cities, the rate could have been as high as 13–15 percent.10 Aside from the practical consequences of the outbreak, such as the destabilization of the Roman military and economy, the psychological impact on the populations must have been substantial. It is easy to imagine the sense of fear and helplessness ancient Romans must have felt in the face of such a ruthless, painful, disfiguring and frequently fatal disease.

It is not difficult to understand, then, the apparent shifts in religious practices that came about as a result of the Antonine Plague. While civic architectural projects were put on hold, the building of sacred sites and ceremonial ways intensified.11 Marcus Aurelius is said to have invested heavily in restoring the temples and shrines of Roman deities, and one wonders whether it was in part due to the plague that Christianity coalesced and spread so rapidly throughout the empire at the end of the second century. Human beings, both ancient and modern, tend to be more open to considerations of the divine in times of fear and in the face of imminent mortality. Even today in modern America, while a place of worship is rare inside an office building, there is one in almost every hospital. It seems that the ancient Romans, in the face of an inexplicable and incurable epidemic, turned to the divine. But the gods moved slowly—it would be another 1,800 years before the smallpox virus was finally eradicated.

“Classical Corner: The Antonine Plague and the Spread of Christianity” by Sarah K. Yeomans originally appeared in the March/April 2017 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review.

Sarah K. Yeomans was the Director of Educational Programs at the Biblical Archaeology Society. She is currently pursuing her doctorate at the University of Southern California and specializes in the Imperial period of the Roman Empire with a particular emphasis on religions and ancient science. She is also a lecturer in the Department of Religious Studies at West Virginia University.

Sarah K. Yeomans was the Director of Educational Programs at the Biblical Archaeology Society. She is currently pursuing her doctorate at the University of Southern California and specializes in the Imperial period of the Roman Empire with a particular emphasis on religions and ancient science. She is also a lecturer in the Department of Religious Studies at West Virginia University.

Notes:

1. This modern term for the second-century plague in Rome comes from the dynastic name of the emperors at the time. Marcus Aurelius and his co-emperor Lucius Verrus were both members of the Antonine family. Because of Galen’s surviving case notes that documented the symptoms of the disease, the epidemic is sometimes referred to as the “Plague of Galen.”

2. Galen, Aelius Aristides, Lucian and Cassius Dio were all first-hand witnesses to the epidemic.

3. Richard P. Duncan-Jones, Structure and Scale in the Roman Economy (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990), p. 72; Richard P. Duncan-Jones, “The Impact of the Antonine Plague,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 9 (1996), p. 124.

4. James H. Oliver, Greek Constitutions of Early Roman Emperors from Inscriptions to Papyri (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1989), pp. 366–388.

5. For further discussions of papyrological evidence, see R.J. Littman and M.L. Littman, “Galen and the Antonine Plague,” American Journal of Philology 94 (1973), pp. 243–255; Duncan-Jones, “Antonine Plague”; R.S Bagnall, “Oxy. 4527 and the Antonine Plague in Egypt: Death or Flight?” Journal of Roman Archaeology 13 (2000), pp. 288–292.

6. The same cessation of construction is not, however, evident in Spain or in the North African provinces outside of Egypt, possibly indicating that certain areas of the empire were more affected than others. See Duncan-Jones, “Antonine Plague.”

7. Dominic Perring, “Two Studies on Roman London. A: London’s Military Origins; B: Population Decline and Ritual Landscapes in Antonine London,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 24 (2011), pp. 249–268.

8. Until recently it was thought that the Antonine Plague could possibly have been a measles epidemic. However, recent scientific data have eliminated this possibility. See Y. Furuse, A. Suzuki and H. Oshitani, “Origin of the Measles Virus: Divergence from Rinderpest Virus Between the 11th and 12th Centuries,” Virology 7 (2010), pp. 52–55.

9. Dio Cassius 73.14.3–4; for a discussion of the smallpox pathologies, see Littman and Littman, “Galen.”

10. Littman and Littman, “Galen,” p. 255.

11. Perring, “Two Studies.”

Related reading in Bible History Daily:

Doctors, Diseases and Deities: Epidemic Crises and Medicine in Ancient Rome

Ancient Pergamon: City of science … and satan?

Justinian Plague Linked to the Black Death

Classical Corner: A Comet Gives Birth to an Empire

This Bible History Daily feature was originally published on March 13, 2017.

Get more biblical Archaeology: Become a Member

The world of the Bible is knowable. We can learn about the society where the ancient Israelites, and later Jesus and the Apostles, lived through the modern discoveries that provide us clues.

Biblical Archaeology Review is the guide on that fascinating journey. Here is your ticket to join us as we discover more and more about the biblical world and its people.

Each issue of Biblical Archaeology Review features lavishly illustrated and easy-to-understand articles such as:

• Fascinating finds from the Hebrew Bible and New Testament periods

• The latest scholarship by the world's greatest archaeologists and distinguished scholars

• Stunning color photographs, informative maps, and diagrams

• BAR's unique departments

• Reviews of the latest books on biblical archaeology

The BAS Digital Library includes:

• 45+ years of Biblical Archaeology Review

• 20+ years of Bible Review online, providing critical interpretations of biblical texts

• 8 years of Archaeology Odyssey online, exploring the ancient roots of the Western world in a scholarly and entertaining way,

• The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land

• Video lectures from world-renowned experts.

• Access to 50+ curated Special Collections,

• Four highly acclaimed books, published in conjunction with the Smithsonian Institution: Aspects of Monotheism, Feminist Approaches to the Bible, The Rise of Ancient Israel and The Search for Jesus.

The All-Access membership pass is the way to get to know the Bible through biblical archaeology.

The post The Antonine Plague and the Spread of Christianity appeared first on Biblical Archaeology Society.

0 Commentaires